News

Latest Lion Aid News

Armed conflicts and wildlife do not mix say two recent articles

Monday 15th January 2018

|

The first, published in 2016, concludes that achieving biodiversity targets in volatile regions will require greater initial investment and benefit from fine-scale evaluations of conflict risk. This article also makes the point that it is actually useful for foreign donors to invest conservation funds in high-risk areas where biodiversity is high – the authors specifically mention the DRC. The article also mentions that such investments, despite the high potential benefits, are scarce because investors are “risk-averse” – donors might challenge money placed in projects that do not always show dividends. In other words, conservation agencies and development agencies are geared towards showing “successes” and therefore are likely to avoid areas at risk in favour of areas of stability that might not benefit goals of overall biodiversity conservation. Of course, it needs to be asked to what extent foreign conservation organizations and local wildlife agencies would “risk” staff working in or near conflict areas? African Parks, for example, withdrew from their project in Gambela National Park in Ethiopia due to instability spreading across the border with South Sudan (see below). My assessment is that we need to do both – accept a measured level of risk in conservation projects as well as maintaining areas where wildlife is already relatively safe. The second article that assessed impact of conflict on wildlife populations used a diversity of statistical methods to reach the conclusion that wildlife population trajectories were stable in peacetime, fell significantly below replacement with only slight increases in conflict frequency, and were almost invariably negative in high conflict sites.

I have some concerns about the methodologies used by the authors to evaluate impact (many of the areas were already very low in diversity and much of the data used came from outdated and anecdotal information), as well as the ability of the methods used to pin declines in wildlife to any particular cause like civil strife. For example, stable countries like Tanzania have suffered tremendous declines in wildlife due to what amounted to almost state-sponsored poaching of elephants and by turning a blind eye to rampant commercial bushmeat poaching. Poaching cartels also operate with various degrees of impunity in Kenya, Zambia, Zimbabwe, South Africa, Angola, Namibia, many western African states – targeting commercially valuable species like elephants and rhinos as well as bushmeat.

In Rwanda, Akagera National Park became destitute during the genocidal events that caused the deaths of between 500,000 to 1,000,000 people in the country in 1994. Due to land shortages, in 1997, the western boundary was re-gazetted and much of the land allocated as farms to returning refugees. The park was reduced in size from over 2,500 km2 to the current size of less than 1,150 km2. Expensive reintroductions, funded in part by the Buffett Foundation, are now revitalizing the area.

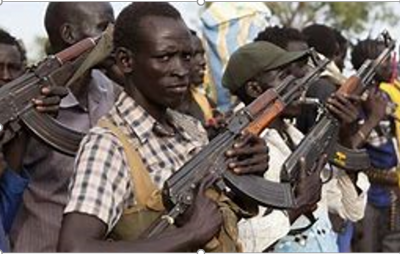

Current areas of wildlife concern include South Sudan, a state currently experiencing massive civil strife and human population displacements. War and civil strife seem to be the order of the day in the region as there were conflicts in 1956-1972, 1984-2005, and the current situation which dates back to 2013. There seems to be no foreseeable end to this conflict, and meanwhile South Sudan’s people and wildlife suffer.

In summary, there can be no doubt that armed conflict is inimitable to wildlife conservation. But even in “stable” countries, wildlife is threatened by corruption, commercial poaching at times facilitated by “stable” governments themselves, non-enforcement of even lax illegal wildlife trade laws, land grabs of nationally protected areas, cattle invasions, assignment of mining concessions within protected areas, etc.

Picture credit – Rappler.com Tags: Africa, wildlife, Mozambique, South Sudan, Ethiopia, armed conflicts, African Parks, Rwanda Categories: Events/Fundraising, Domesticating Animals |

Add a comment | Posted by Chris Macsween at 14:17